About 25 years ago, I was working mainly in paint and collage, with some printmaking, ceramics and other mediums tossed in. I put my work on display at cafes, in small art festivals and bazaars, and even sold some items through consignment in art shops, and I made just a little extra money that generally went straight into more art supplies. It was a hobby that barely supported itself.

One day, I took a portfolio of artwork and a stack of handmade art cards and headed to a gallery that I liked, having arranged to meet with the owner/curator. After flipping through the work, she said, smiling, “I’m afraid your work isn’t a good fit for our gallery. We sell art that people would want to put on their walls.”

I felt stung. I wanted to take it all home and burn it, then crawl into a manhole and just live there forever. I had become accustomed to hearing people’s opinions of my work during exhibits and festivals, and I had learned to appreciate that everyone reacted differently to my art. Some liked it and some didn’t, and I never took it personally, but that snarky gallery owner’s jab really hurt.

Luckily, I was accompanied by my then-boyfriend, and he encouraged me to go for a little walk to a favorite shop, Traditions Fair Trade. Then he suggested I show them my cards, which were a mix of collage and linocuts with sewn elements. They loved them and took them on consignment. For a long time, I kept restocking their card rack and received a small check every month.

The thing is, I now look back on the artwork I took to that gallery and it was BAD. I hadn’t found my mojo, my medium, and it really wasn’t marketable. She didn’t need to be so mean, but she was making a good call. (By the way, I married that boyfriend, also a good call.)

Processing rejection has become a necessary part of the work I do. You can’t move forward without taking risks, and there will always be false starts and wrong turns. It’s important to be able to assess whether the rejection means you were barking up the wrong tree, or are you just not at the level you think you are? Seeing your own work objectively is very difficult. Sometimes it is only clear through hindsight. But try to set aside your personal attachment to the art, what your intention was, how much work went into it, and try to see it as if you are a stranger. Is it something you would buy? If so, what is your demographic and what kind of space would it enhance? That might help you to market to a receptive audience.

I’m writing this while processing a recent cluster of public art rejections. For those of you who aren’t pursuing public art projects, opportunities are posted on various list forms, and artists can apply for the ones that seem appropriate. It takes a lot of time to scroll through these lists, read all of the goals and eligibility requirements to determine which are worth applying for. Then, we spend hours or days writing letters of interest and art statements, uploading images and descriptions, and whatever else is required. I apply for about 30-50 RFQs each year. They seem to be released in waves, so there are times I’m trying to get several done within a couple of weeks. Once they are submitted, I try not to think about it because the chances of being selected or shortlisted is quite slim, especially before you have a strong portfolio.

And, to be clear, you build the portfolio by getting selected, so it’s a chicken and egg situation. Established artists have a significant advantage and it takes forever to become established. It is not uncommon for RFQs to only allow previous public art projects and NOT privately commissioned or non-commissioned artwork in your work history, effectively eliminating anyone without public art experience (and preventing them from getting any).

Timelines for this process vary widely. Ideally, the art committee sends out the RFQ at least a year before they expect to receive the work, because the whole process is very long and complex. Last July, I applied for a large project to honor veterans. I submitted, then put it out of my mind. Later, in early fall, I applied for something with a modest budget, but in my county, which is unprecedented. I live in a rural area that doesn’t usually receive public art funding, so I was excited by the idea of installing something in my own community. On my birthday at the end of November, I got the call that I was shortlisted for one of the projects, and soon after, I was shortlisted for the other. Exciting! (Shortlisted means they picked a small number of candidates who are then paid to develop a proposal, usually 3-5 of the applicants.)

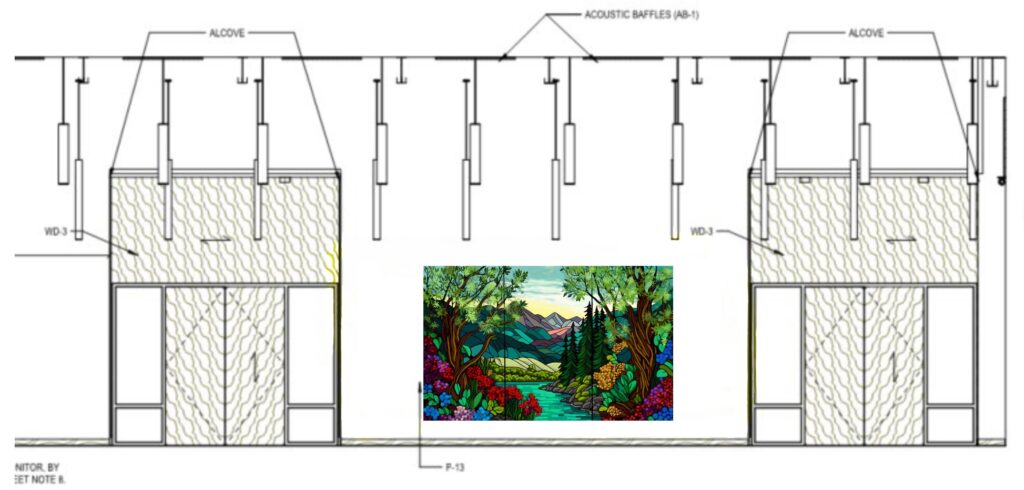

I was just starting on my current project, which is the largest I’ve ever done, and it was just before winter break, the holidays, and a trip to MX. The smaller, more local proposal was due first, so I was trying to work on that while also keeping up with the project on my work table, and managing holidays and life. The scope of the project was far bigger than the budget would allow in mosaic, so I went through a number of iterations. It could be done faster and cheaper in paint, but my painting skills are not great. One of my designs is something I really love, but I couldn’t have done it within budget. I came up with a simpler design and a plan to fabricate it through community engagement, by holding events/workshops on the campus where it would be installed. I managed to get it submitted by the deadline in mid-January. I knew the design wasn’t going to knock anyone’s socks off, but if selected, I could develop it further.

In early February, I received the notice that my design wasn’t selected. I was actually a bit relieved. I realized that a community-made mural was probably not the best fit for the space, which was between two entrances to a big conference hall. Participatory projects are uncontrolled and this needed to be a high quality artwork. I’m certain the selected artist was a better fit.

So, by then, I was way behind on the proposal for the larger Veterans Memorial project. This one would have been the biggest commission of my career; a set of sculptures in a lovely setting. Again, I worked through multiple design concepts. Abe Singer, who worked with me on the sculptures in Edmonds in 2022, was going to be my collaborator again. But then he was selected for his own big project, which will occupy his time and studio space. So, I floundered for a while, trying to figure out how to have the substrate fabricated. My friend and esteemed colleague, Jill of Jill Carter Designs, helped me hone my proposal, which was for two sets of abstracted steel flames inset with gold smalti mosaic. I did line up a fabricator, paid an engineer to work out an installation plan, and by the end, I had fallen in love with this design.

For this proposal, I had to present in person to a large panel that included arts administrators, city officials, and community members (including veterans). The week before it was due, my daughter’s transmission failed, which meant our family had to juggle cars and since I work at home, I’ve been carless. I had to rent a car last weekend for the drive. As I left home, a bald eagle swooped down in front of the car, coming straight at me before lifting up and over me. I swear it looked right at me. The magical thinking part of me took it as a good omen. I had booked a room in the hotel overlooking the park and lake where the sculptures would be installed. On arrival, they told me I had been upgraded, and I had a very nice room on the top floor with a balcony. I walked around the site, explored the area, then sat on the balcony imagining my artwork below with the angle of the light shifting at different times of day. I ate dinner at a restaurant bordering the park. It felt right and I thought I had a great shot at getting the job.

In the morning, I gave my presentation. I felt confident and energetic, genuinely excited about the proposal. The sun was shining. I then met up with my friend and mosaic/ceramic artist Karen Rycheck (https://breadandbutterstudios.com/) who was kind enough to listen to me rambling enthusiastically about the proposal through lunch. Then I drove home feeling relieved and hopeful that this would be my 2025 project.

While I waited for the result, I focused on the work at hand, happy to spend more time in the studio making progress on the mosaic. I spotted another compelling RFQ, however. This one is more than twice as large as anything I’ve completed so far, is only a little over an hour from me and is something I would love to do. And it was due within a week. With only a couple of days to spare, I decided to go for it. I took half a day off from the studio to submit all of my materials. The installation goal for that one is early 2026, so it would be possible to do both. And I’m glad I did take that time because I learned two days ago that I was not the selected artist for the veteran-themed sculptures.

I have to confess, I pouted. I was bummed out.

The next morning, I pulled it together and sent a note of thanks to the administrator, and I asked if there was any constructive criticism about my proposal or delivery, and could she share the name of the selected artist. It turns out, the person chosen has a longstanding career creating metal sculpture for veterans and war memorials, along with a solid family history on the side of good with the Holocaust. He has his own wikipedia page and a quote from Joe Biden describing him as the “finest American sculptor” for his work on a prominent memorial in New York.

My first thought: I never had a chance! I put all of that time and energy into something I was never going to get!

My second thought: Wow! I was being considered for a project alongside an artist of this caliber! I am honored and humbled!

And finally: I had the opportunity to present myself to the people influencing the ongoing development of a new city hub that will incorporate more art as it is completed. They will remember me next time. And maybe I can use my proposal for another RFQ, as appropriate.

I sat down today to write a much more succinct post for artists interested in following the public art path, to elucidate the amount of time we have to spend submitting for opportunities. It’s like having to constantly apply for a new job, over and over. I have to watch out for jobs and apply for them while I’m still doing a different job. Some jobs expect to be happening in a year or two. Way too often, the administrators don’t plan ahead, and they expect to hire you immediately and install the next quarter. Lower budget projects are usually managed by less experienced administrators with unrealistic expectations. I find that the folks asking for a $25,000 project tend to want something of a similar size and scope of those with a $75,000 budget. And in a fraction of the time. So, it’s a lot of juggling and managing expectations, and it’s a constant hustle. But, in the long run, having a commission that will provide job security for 6 months or a year is worth it, in addition to the satisfaction of creating something for public enjoyment. Larger budget projects also give me a chance to stretch my abilities, to hire collaborators, to bring visions to life that I could never afford to do without the financial support.

I can’t believe you read this far.

Oh, and I wanted to share my artist friend Carrie Ziegler’s post on rejection, which addresses the topic through her own perspective. She’s a good writer and a very insightful person. This was posted on LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/art-rejection-move-through-align-your-calling-carrie-ziegler-jzsmf/?trackingId=YPeyPBEPSgatO54f2XrIig%3D%3D